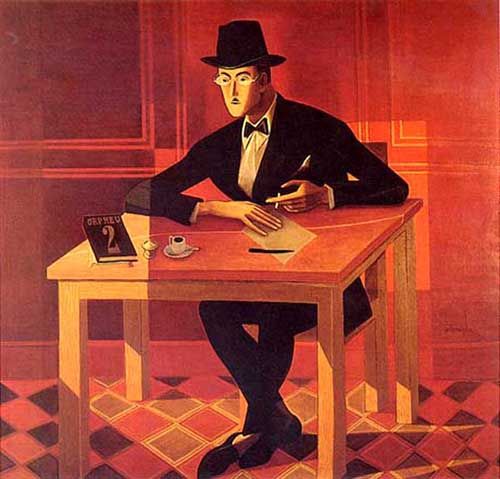

Written by Fernando Pessoa

Translated by James Crosby

The reader should take note that, within the various heights of this volume, we have filled the spaces between the ends of each paragraph and each page with brief precepts, maxims, and considerations of a diverse order, with a proclivity to suggest, and insofar as we can truly cover here, rules for a life in reality, distinct from those which have only a moral or educative consequence. Having been rated favorably by many readers, this volume has also been referenced in other editorials, and in the same manner with which we have raised with levity or with irony the tone of one or another source to which we have referenced here.

How much of a humorous tone certain quotes and precepts may have, we have no desire to defend them with explanation, as it is more valid to expose something through levity than through pedantism. The truth is not less true when said with a smile than with an air of severity, in the same manner that an argument does not carry more weight when it is stated in erudite language than when it is stated in simple language. It is a question of modes of speaking, and nothing more.

What is more interesting however, as it is more complex, is the problem which arises in turn from nature, which at times appears crude and almost cynical, and for which here we have cited precepts with both succinctness and with italics. We believe that it is this which compels us to, by the close of this volume, give a brief explanation on the subject. And it is this explanation that serves as the motive for the presentation of certain new precepts, whose particular interest participates in the general interest for which we pretend to give this article.

Man supposes itself to be a rational animal. This can be fact and this can be unfact: the field of psychology contests the importance and the preponderance of reason in an individual life. There are, she says, instincts, habits, sentiments, and emotions that undoubtedly guide man; for which reason does not serve if not to interpret the volition of these subconscious impulses. But the fact is that the primary state of man is to consider himself an essentially rational being, if only in an indirect manner, and that reason assumes a primary importance in his life. On occasion, one of the abstract works of reason is to put forth precepts, maxims, or intellectual norms for conduct, general or particular, in life.

These precepts are of three orders, which we may call: (1) Moral Precepts, (2) Rational Precepts, and (3) Practical Precepts. Moral precepts propose what we should do to keep well within our consciences. Rational precepts propose what we should do to keep well within our lives. And practical precepts propose what we should do to keep well within our ambitions. The first are, as is self-evident by the name we have given them, invariably morals in the manner in which they are postulated. The second are simply what may be called ‘sensible’, or common sense. The third are, in many cases, rarely moral, and, furthermore, hardly sensible, and it is for this reason that life, in practical reality, is frequently immoral, and not the least bit absurd.

There are four examples that describe these three cases.

Example of a moral precept:

“Do not do unto others what you do not want done unto you.”

Example of a rational precept:

“Know thyself.”

Example of a practical but hardly moral precept:

“If you want to deceive someone in a formal negotiation, deceive them before any communication has begun, for otherwise they will lie to you with conviction.”

Example of a precept that is hardly ‘sensible’:

“He who leaves nothing to chance will do few things poorly, but he will do few things.”

The first precept is, in one form or another, a central tenet of diverse religious systems. The second, an inscription found on a Greek temple, is attributed to a Greek philosopher that probably never existed. Of the last two, the first is from the Florentine Francesco Guicciardini, and the second from the Englishman Marquess of Halifax.

In these corresponding popular Portuguese precepts, to which we call proverbs, we find three orders of maxims.

A moral proverb:

“Son you are and father will be, and as you do, so you will find.”

A rational proverb:

“To trust in the Virgin and not run, and the fall you will watch yourself take.”

An example of a practical proverb:

“Whomever the enemy spares is by his hands they will die.”

No one can say that this last proverb, which is a type of recommendation we may call ‘predefensive’ homicide, has moral advantages over the Guicciardini precept quoted above. It is a precept of inferior utility than the Florentine’s, which is a universal ‘truth,’ and the Portuguese proverb only relates to certain avenues and for certain circumstances.

These considerations, which have been illustrated by the examples above, should be clear to all now, and will thus forth serve as the basis for our examination of the problem.

Society is a system of malevolent egoisms, and of intermittent harmonies. Each man is, in the same moment, an individual being and a social animal. As an individual he distinguishes himself from all other men; and because he distinguishes himself, opposes them. As a social animal, he presents himself as all other men, and because he presents himself as such, groups with them. The social life of man is divided into two parts: one part individual, and that flows in concurrency with others, and for which he must therefore remain on the defensive or the offensive in relation to them, and one part social, in which he resembles them, and therefore has only to be useful and agreeable with them. To be on the defensive or offensive, he must see clearly what others really are and what they really do, and not what they should be or what would be good for them to do. To be useful or agreeable, he must simply consult man’s pure nature. The exacerbation, in any man, of one or the other of these elements inevitably leads to his complete ruin, and therefore to the very folly of the intention of the predominant element, which, as it is part of man, falls with his fall. An individual that conducts their life within the lines of a moral purity and righteousness ends by feeling infringed upon by everyone - even by individuals who, also being moral, are less high and less pure. And this resentment, this bitterness, this disillusion that accompanies a moral nature, will be the outcome of his experience. But as well, an individual who conducts their life within the confines of a constant delusion finishes in a prison where few can intrude, or where because of their mistrust of everyone, no one has the power to intrude on them.

It is at times because of this dual nature of man that precepts of a dual nature have arisen; one guides the formation of man as a moral or social being; the other advises his education in Grand Strategy. The precepts which we call ‘rational’ occupy the space in between; they do not direct the cosmogony of society, nor guide the education of the ego. They are rules for a harmonious and quiet life, one that does not transgress upon others, nor upon one’s self.

What constitutes, then, the essence of a precept is the desire to instruct particularly the development of man as a moral or social being, and the desire to guide especially the development of man as an individual ego. The precept always speaks within the existence of the other nature of man. As reality has two elements - the moral and the practical - the moral precept always speaks within the existence of the practical element, and the practical precept always speaks within the existence of a moral element. The moral precept, to be truly a moral precept, must never forget a certain limit. The practical precept, to be truly a precept, must never forget a certain moral law. In this way precepts, which are for the most part just sayings, are distinguished from mystical religious rules on one side, and cynically absurd inclinations on the other. The precept, moral or practical, is the midway point between Sermon on the Mount and the Manual for the Perfect Heist. As for the precepts that we call rational, there is no need to elaborate on their centrism, because this elaboration is already present in the definition we gave them above.

Let us now propose that we begin the study and explanation of the precept which we call practical - that precept which frequently appears immoral or insensible. We are already, following the brief explanation we have given, in position to define it. A practical precept is a rule of conduct for the ego that does not forget the dual nature of man, nor the balance between these two elements. There are situations or circumstances in which, through their proper nature, the moral element does not figure; the precept that is established for these will necessarily be immoral. There are situations or circumstances in which, through their very nature, the practical element figures poorly; the precept that is established for these will be necessarily moral. There are situations or circumstances, almost always abnormal, in which, through their innate nature, disrupt the natural balance of things; the precept that is established for these must recommend what to do in order to return to equilibrium, a disruption in the opposite direction, and thus resulting in a precept that seems ‘insensible’.

These explanations which, departing from clarity, are abstract, and demand for the reader new examples, which we are going to give, for each type of practical precept that we have mentioned.

Examples of a simple practical precept:

“Everyone sees what you appear to be, few experience what you really are.”

“Do not pay a favor to one that comes at the expense of another, for the first will probably forget the favor, but the second will never forget the injury.”

"Secrecy is like most other qualities; it is necessary, and is, at the same time, dangerous. To not have any makes one despicable; to have it in excess makes one suspicious. There is nothing, however, noble in this quality, for often it is the case that an ordinary chambermaid possesses far more of it than any prince.”

“If you are going to do harm to someone, or if you decide to do someone harm, do so to the fullest extent that you can. It is better to kill a man than to mortally injure him, as the dead do not think of revenge. Men are always more ready to return an injury than a favor, for to return a favor is an obligation and to take revenge for an injury is a pleasure.”

All of these moral principles are from Machiavelli and, it should be noted, were principally written for politics during an age of subterfuge and tumult. But, save in rare social circumstances in which they absolutely do not apply, these principles are absolutely true.

Example of a practical precept that is necessarily moral:

“Honesty is the best policy." (English proverb).

Examples of practical precepts which are necessarily 'insensible':

“In the greatest of challenges, act always before you think.” (Anonymous).

“That which has no solution, is already solved.” (Portuguese proverb)

With the explanations we have already given, and the examples we have now finished giving, the reader should have a firm grasp of what is essentially a practical precept. And with this understanding, we will have absolved ourselves of the little that could seem cruel or cynical in any of the brief maxims we have placed at the bottom of these pages.

Thanks to this, which was the first part of what we promised to do in this study, we can now cover the other part for which we promised. We will now present the last group of practical precepts that have arisen in public. Their appearance has been more than recent, in fact almost synchronous. We devote these new precepts, of a predominantly industrial nature and, for this, the focus of this magazine, to the great American businessman, the supreme millionaire of the world, Henry Ford.

The most useful practical precepts, as one would expect, are the product of men not more intelligent than they are practical, but more practical than they are intelligent. The greatest masters of practical precepts were politicians who reflected on politics; as was Machiavelli, whose precepts illustrate what is evil and bad in all men; as were George Seville and Marques de Halifax, whose maxims illuminate what is frankly human in all people.

From Henry Ford then, captain of industry, one would expect to find precepts that elucidate the essential conditions of modern leadership, at least in the particular fields of industry and commerce. Real life therein, where people live today, has, or at least seems to have, a greater character of hypocrisy than the Italian Renaissance or the English Restoration. The practical precepts that Henry Ford gives us seem to be the result of only that half of his experience which has been shared with us. They loosely participate in the spirit of prohibition. They have been served to us with water.

Such as they are however, it is still worth the pain to read them.

In their original form - in the last of the various books that Henry Ford has published to explain his life and complain about his cars, they are dispersed and uncoordinated. Lord Riddell gave himself to the work of compiling and clarifying them. It is, then, in redaction of Lord Riddell that we give the 9 industrial mandates from the American Multimillionaire. They are:

- Search for simplicity. Examine everything constantly to see if you can simplify something or perfect something. Do not respect the past. Just because something has always been done in a certain manner does not mean there isn’t a better way of doing things.

- Do not make theories, make experiences. The fact that past experiences have not shown results does not mean that future experiences will not. Experts are slaves to tradition. It is therefore better to entrust the research of new projects to energetic people of first-rate intelligence. Let the experts serve them.

- Work and the perfection of work should take precedence over money and profit.

- Make the work in a most direct manner, without the necessity of rules and laws, and without the vulgar divisions of discipline.

- Install and maintain all of your equipment in the best state possible and keep each part in a state of absolute cleanliness. In this way a man learns to respect their tools, their environment, and the next man after him.

- If you can manufacture something which you must use in great quantities at a price lower than what you can buy it, make it.

- Wherever possible, replace man with machine.

- The business does not belong to the owner or its employees, only the general public.

- The fairest salary is the highest salary that a boss can offer to pay regularly.

These rules - having now been stated and maintained - represent only half of the industrial and commercial experience of Henry Ford. Of the other half, which must have contributed no small part into making him the super-Rockefeller he is today, he will perhaps never reveal those commandments.

We will content ourselves to these which, in their own right, are admirable. They contain teachings that the majority of our industrialists could, without betraying their first loves, hold dear in their minds and in their memories. We will not comment further on these precepts, which, moreover, do not require comment. Only to the last of them, or at least to their derivative in Ford’s recent industrial mandate - will we speak on to close this article.

Henry Ford has just finished implementing in his factories the five day work week. He has just proposed a consideration to the world, as an example to follow, of the philanthropic reduction of work for his operators. What follows, however, and what is already known, is that the manufacturers of other cheap American cars are gaining on the sales of Ford automobiles; while for years Ford produced more than half of all cars manufactured in the United States, he now produces only about thirty-five percent of the total; Ford factories are therefore confronted with the problem of overproduction, forced to produce at only sixty-five percent of their capacity, and forced to work only forty hours a week..

As luck would have it, to proclaim to the world a new economic motto and moral in the five-day work week, Henry Ford, without having to invent for himself a new practical precept, limited himself to follow that which is most admirable from the master Machiavelli:

“What we do out of necessity, we must make seem it was of our own volition for which we did so.”